Community Economic Development-Social Sustainability Model for 21st Century Local Policy-making

This essay is the second part of a larger project focused on defining and connecting social sustainability and community economic development in order to inform local policymaking to further improve communities’ ability to fully mobilize and achieve sustainable development. This essay connects the concepts developed and defined in the previous essay and fully builds the CED-SS model. The main forum for this project is through the Wordpress blog, “Nexus Point: Social Sustainability and Community Economic Development.” Follow along with the twice-weekly posts that will explore this connection and what that looks like for both urban and rural communities.

The Connection between Community Economic Development and Opportunity

Now that we have definitions for community economic development, “opportunity for all,” and social sustainability, the next step is to begin to build the connections between them to arrive at our full CED-SS model.

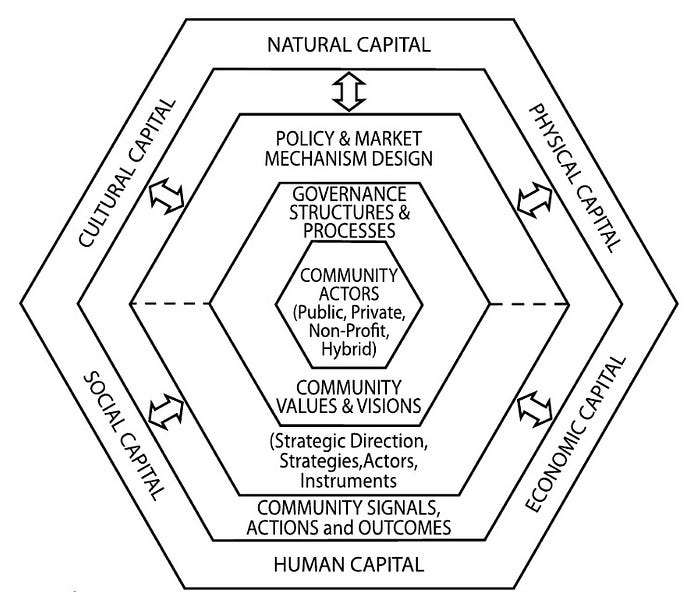

Looking at community economic development through the lens of Roseland’s matrix of actors and mechanisms at play in community economic development’s interaction with the community capital framework, we can see that the policy intervention is the starting point and main mobilizer for the CED-SS model. It is the mechanism through which the involvement of members of the community, motivated and guided by these community factors, mobilize for improvements in their community capital stocks. Community engagement in the local policymaking process is the key component required for this model; without it, its full potential won’t be reached.

These policy interventions, influenced by the community factors that Roseland posits in the center of his hexagon (while I place them in the CED bubble below) primarily take aim at one of the six community capital stocks; however, that improvement will have a positive ripple effect through one or more of the other capital stocks. These improvements in the community capital stocks lead to an improvement in the quality of life for community members and fosters opportunity for all. This is the link between community economic development and opportunity.

The Connection between Opportunity and Social Sustainability

Opportunity is at the center of the model, and we saw it is supported and enhanced through community economic development. “Building opportunity for all” and “quality of life over time” are the two prominent pieces of the definition of social sustainability as we defined it above. We’ve already fleshed out what opportunity for all looks like, and everyone interprets and defines quality of life in their own subjective way. To complicate things further, there’s no universally recognized scientific definition upon which to base any analysis.

However, just sort of intuitively, most people see it as a measure of the positive and negative aspects of life, generally. There are a number of components that are a common thread throughout the literature on the quality of life, including:

· Health

· Jobs

· Housing

· School/education

· Neighborhood

· Culture/values

· Environmental quality

· Material status (commodities, services, purchasing power, etc.)

· Level of acceptance of current condition

· Ability to regulate negative thoughts and emotions about current condition

Even just a cursory scan over these components shows clear ties to the community capital stocks that we’ve built into our model, tying back into our definition of community economic development: “an enhancement of the community capital stocks through a community economic development policy intervention leads to opportunities for all.” Because of the broad overlaps between the components of quality of life and the community capital stocks, there is a link between opportunity and quality of life: increased access to a vast array of good opportunities leads to improvements in quality of life in a community. It’s imperative, then, that both community economic development and social sustainability are understood as intertwined in and essential to the local policies that mobilize sustainable development from community to community.

A Case Study of the CED-SS Model as a Policy Evaluation Tool

The CED-SS model is primarily aimed at being a framework to look at creating new policies in a community. It can also be used, however, to evaluate past policies to extract lessons for future policymaking so that it can fully maximize opportunity and foster strong social sustainability.

Let’s take a look at a case study where there was a breakdown in the model and an impending erosion of social sustainability in the community to highlight some of these lessons: the demolition of the Hershey chocolate factory in 2012.

The Hershey Company is the largest chocolate manufacturer in North America and one of the largest in the world; it’s tough to find a place where you can’t find a Hershey bar. It was founded as the Hershey Chocolate Company in 1894 and production began at the turn of the 20th century. The original factory was built in 1903 and was the only place in the world where any Hershey products were made for 60 years.

Meanwhile, the town of Hershey grew alongside the company that provided its foundation. For Milton S. Hershey, “developing the community became a lifelong passion,” as he wanted to build a model town for his employees that offered numerous opportunities for them and their families. The factory at 19 East Chocolate Avenue, however, was always the heart and soul of the town as it was the birthplace of the idea of the town and the main employer and driver of development in the community.

The factory symbolized and embodied the town, the lasting legacy of Mr. Hershey and his vision for the community. It was a reminder of the history that was made at that factory over its century-plus lifetime.

There are many stories, both on the Internet and with the countless people who have both lived in Hershey and those who have come to visit its attractions, of how the factory was special to them, in their own unique individual way.

That’s why there was such a strong reaction from the community when, in 2012, the Company announced its intent to demolish the majority of the factory buildings (many of which were not necessarily original to the factory, but had been built during expansions throughout the past century) and build new office spaces for its employees. The Company cited competitiveness and finances as the main reasons for the move.

So, let’s start looking at what happened in 2012 through the lens of the CED-SS model:

In the CED block at the bottom of the model, there was strong community engagement and mobilization in the local policymaking processes in response to the Company’s plans: there was an online petition to preserve the cultural capital value of the factory to the community and redevelop it to be used for all members of the town, and 60 local residents attended the November 5, 2012 meeting of the Derry Township Design Review Board when the Company’s proposal was being reviewed and voted on. The aim of these signs of community mobilization were aimed at influencing the policy intervention, or, in this case, the approval by the Design Review Board of the demolition of the factory at 19 East Chocolate Avenue.

Here, however, is where the SS-CED model was not followed and begins to break down: the policy intervention that resulted was not responsive to the voices of the community. In the Design Review Board meeting, Supervisor Sandy Ballard asked for a 15-day review of the proposal and a vote at the next meeting in order to address the concerns of the community. She was overruled by the rest of the Board.

The proposal to demolish the factory passed that night by a vote of 4–2. This sent a signal to the community that the Company held more power in the local policymaking processes and arenas than the residents of Hershey did. This drastically lopsided power balance wouldn’t exist in a community that had strong social sustainability and responsive local government actors.

The approval of the proposal was, if looked at through the CED-SS model, a misguided attempt at improving the economic capital of the community; however, in reality, it improved the economic capital of the Company and allowed it to make the easiest, most cost-effective decision for their interests without taking into account the best interests of the community. This, in turn, eroded some of the cultural capital in the community as its heart and soul was demolished and replaced with office spaces that are hidden from view from Chocolate Avenue and not designed for public use.

Moving from the “CED bubble” to the “opportunity bubble” in our model, the demolition of 19 East didn’t necessarily bar anyone from opportunity; it did, however, forgo wide potential for building new opportunities for all members of the community. If the Company and local government were really motivated by the community’s interests, there would have been an effort made to repurpose at least part of the property into a space that could have fostered small business growth or new services and meeting places for the community while still maintaining (at least partially) the cultural capital in the community.

Many of the residents recognized that, as former Chairman and CEO of the Hershey Company Dick Zimmerman said, “economics have to prevail” and production couldn’t be continued at the old factory. However, they would’ve rather seen it (or a portion of it) maintained and opened up to the community in order to preserve that part of the town’s history and culture. The Company would have still benefitted in this case and the community could have seen improvements in any or all of its community capital stocks; the two stakeholders involved could have happily compromised and both been better off, in terms of how the model works.

That wasn’t the case, though. What resulted, an implicit repudiation of the strong community engagement on the issue, led to an erosion of social sustainability in the town: looking back at our definition, the demolition of the factory and subsequent replacement of offices actually damaged some of the community capital and did not lead to the “continuous enhancement of every individual’s quality of life over time.”

And, finally, the interaction between social sustainability and community economic development at the tail-end of our model. Because the social sustainability of the town was eroded, community members became more disengaged and cycnical about the Company, their local government, and their ability to influence the policymaking process to advocate for their interests. This, ultimately, leads to further breakdowns in the CED-SS model in future policy interventions, as the inputs necessary for successful policymaking are not whole and mobilized.

Visit the blog to explore more at https://nexuspointblog.wordpress.com/.